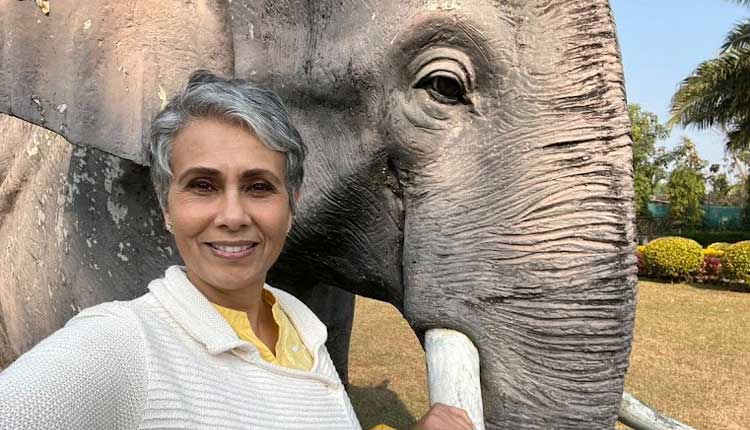

New Delhi: As the world observes Elephant Day on August 12 to raise awareness about preservation and protection of the largest land mammals, a top Indo-Canadian conservationist says India has miles to go when it comes to saving their gentle giants.

With almost 1,200 elephants killed in the last 10 years across India — 245 of them in the past three years in Odisha alone — the gentle giants are at a grave risk, with just 27,000 left in the country at present.

And with Kerala losing 58 per cent of its wild elephants in the last six years, according to a 2023 forest department data, there “seems no sense of urgency to implement solutions and deal with a crisis unfolding in India,” says multiple award-winning wildlife filmmaker and elephant conservationist, Sangita Iyer.

“India still has a long way to go when it comes to elephant conservation, and appreciating the interdependencies of every creature in this magnificent web of life,” Iyer, founder of Voice for Asian Elephants Society (VFAES), told IANS in an interview.

The pressing issues

According to Kerala-born Iyer, India has some of the best wildlife protection laws, but they are not being enforced.

“The recently amended Wildlife Protection Act 1972 (Section 43) allows the transfer of elephants between states, creating loopholes that will be exploited, potentially emboldening illegal elephant captures. Additionally, even the existing laws are not being enforced,” she says.

Citing the tragic case of a pregnant elephant in West Bengal, who died last month after officers allegedly darted mistaking it for a bull elephant, Iyer rues that many untrained forest officers are given the task of protecting elephants, wildlife and the natural treasures of India, which is causing a lot of harm.

“What a heinous crime against nature is this!! Now, the question is, will these officers be held accountable? Will they face the seven-year jail sentence as per the Wildlife Protection Act?”

Along with British MP Henry Smith, Iyer had addressed the UK Parliament in June, imploring Indian authorities to act urgently in the wake of the alarming number of elephant deaths caused by electrocution, poaching and habitat loss, among other growing threats.

Calling Odisha the “largest elephant graveyard”, Iyer told the Parliament that “electrocution and train track deaths of elephants are happening at an alarming and appalling rate in Odisha where mining and poaching are out of control”.

Rampant mining aside, roadways and railways cutting through core forests, illegal human encroachment and unsustainable extraction of forest resources have resulted in elephants losing 80 per cent of their habitats.

The roar versus the trumpet

This year, India witnessed a surge in the number of tigers, which were endangered and on the verge of extinction due to massive poaching, with mere 1,411 in 2006 to 3,682 in 2022.

Calling tiger conservation in India a massive success story, Iyer says that the Project Tiger authorities did a “phenomenal job” using the funds allocated by the Union government, and in comparison, Project Elephant “seems to have failed miserably”.

“Nobody knows what this unit has achieved over the years, except produce the Gaja report, and conduct elephant census every five years, although even that has been stalled due to Covid. It has now been seven years since the last elephant census was conducted in 2017,” Iyer told IANS.

The need for an elephant census is all the more pressing to understand the elephant gender ratio. According to Iyer, as of now, only 4.4 per cent of the total elephant population in India are males, which is creating a serious gender disparity in the wild.

“At this rate, elephants will become extinct in less than 10 years,” she says.

Simple measures to save precious lives

According to Iyer, there needs to be an authentic acknowledgement of the challenges facing the elephants of India, and a genuine willingness to implement tested and tried solutions that are working elsewhere in the world.

To begin with, she says simple measures like imposing fines for tossing garbage out of the trains would help save elephants, as they can sniff out food from as far as 19-20 km away, using their highly evolved olfactory senses.

Additionally, the decision makers need to be sensitised with awareness programs specific to elephants, their vital role as climate mitigators and ecosystem engineers, and the cascading effects of their disappearance from our planet, says Iyer.

An International Monetary Fund report estimates the carbon value of each forest elephant at $1.75 million.

But of paramount importance, says Iyer, is taming the jobless and unproductive youngsters in the elephant range states in India.

“They simply don’t know what to do with their time. So, they chase and bully elephants, a punishable offence. Yet, hardly any charges have been levied by the state or Central government against them. And a few instances in which charges had been laid, are still pending in the courts,” says Iyer, a Nari Shakti Puraskar recipient.

Haunted by the pain and suffering of Asian elephants, Iyer and VFAES have launched more than a dozen projects in India since 2018 in collaboration with grassroots organisations and state governments.

Some of these include planting saplings and creating waterholes in Odisha forests by employing tribal people; installing road signages and technology to warn truck drivers in elephant crossing zones, and barricading more than 100 open wells in Odisha.

Apart from providing elephant-friendly fencing, Iyer and her organisation have implemented a device called EleSense, which detects the elephant presence around 500 metre.

According to VFAES, between January 1 and July 12, 2023, EleSense has potentially saved 161 elephants in the Dooars region of West Bengal alone. The organisation is now in discussions with the authorities in Odisha to implement the technology.

(IANS)