New Delhi: December 16 holds a significant place in South Asian history, marking not only the anniversary of the Bangladesh Liberation but also a defining moment that reshaped the region’s political and social landscape. This day commemorates the struggle for independence, but it also serves as a solemn reminder of the sacrifices made in the fight for a new nation.

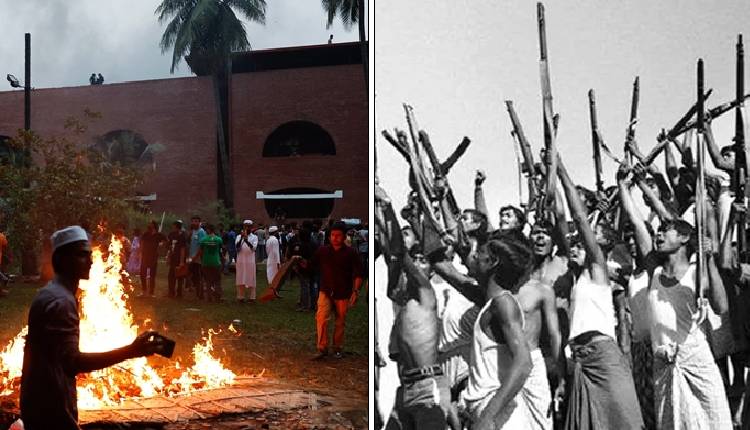

As we celebrate Bangladesh’s victory, it is crucial to reflect on the long-standing plight of its minority communities, particularly Hindus, whose survival has been marked by continuous persecution. The echoes of 1971, when political, geographical, and ethnic struggles led to widespread violence against minorities, still resonate today.

The blood of these marginalised groups has flowed through the rivers of Bangladesh, both then and now, raising a pressing question: is history repeating itself in the ongoing fight for their survival and dignity?

Struggle for identity and justice

In 1948, Jinnah’s declaration of Urdu as the state language of Pakistan disregarded the linguistic majority of Bengali-speaking East Pakistanis, who comprised the largest population group. Jinnah believed that their identity as Muslims should supersede their cultural and linguistic identity, declaring, “The essential condition for the success of Pakistan is complete internal solidarity… Urdu must be the State language of Pakistan.”

This sidelined Bengali identity, fueling deep resentment and cultural suppression despite vague promises of regional language autonomy.

The (West) Pakistanis also perceived Bengalis as racially and ethnically inferior, systematically excluding them from military and administrative services. Despite accounting for 55 per cent of Pakistan’s population, Bengalis had negligible representation in civil, military, and bureaucratic services. The elite of West Pakistan considered Bengalis “lesser Muslims” due to their perceived Hindu cultural influence.

The Pakistani government’s response to Cyclone Bhola in 1970 exposed its apathy. The central government, dominated by West Pakistan, delayed and poorly coordinated relief efforts, further exacerbating tensions. President Yahya Khan visited the affected areas days later but took minimal action beyond declaring a day of national mourning. This indifference highlighted systemic neglect, fueling demands for autonomy.

Decades later, echoes of such neglect persist. During the August 2024 floods in Bangladesh, similar concerns arose. A leading television network shed light on distressing incidents of discrimination against Hindus in relief distribution.

A viral video featured a man from the Hindu community in Cheoria, Tulabaria, in Kalidah Union’s Ward No. 8, Feni district, expressing anguish: “We have not received a single person for relief. Our only crime is that we are Hindus. People in Noakhali and Barisal are receiving aid, but when they see us, they turn away.”

The video underscores ongoing inequities, urging authorities and humanitarian groups to address such biases and ensure equitable relief measures. Temples like ISKCON have stepped in to fill the gap, offering shelter and aid to affected Hindu families.

West Pakistan’s refusal to accept the 1970 election results—in which the Awami League, led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, won decisively—escalated protests in East Pakistan. On March 7, 1971, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman laid out conditions for talks, including troop withdrawal, halting reinforcements, and granting autonomy.

He initiated a non-cooperation movement marked by strikes, tax refusal, and village-level liberation committees. However, these demands for equality were met with violent suppression, culminating in the declaration of independence on March 26, 1971, by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

Operation Searchlight: A genocidal prelude

On March 25, 1971, the Pakistani military launched “Operation Searchlight,” a campaign of terror against civilians in East Pakistan. Intellectuals, students, and cultural leaders were targeted, with cities like Dhaka witnessing bloodbaths. This systematic violence is a stark reminder of how unchecked power can devastate communities.

According to Taqbir Huda’s article ‘Remembering the Barbarities of Operation Searchlight’ in The Daily Star, the campaign began with death squads killing 7,000 unarmed Bengalis in a single night. Military generals in West Pakistan, unwilling to relinquish power, decided that a genocidal campaign was necessary. President Yahya Khan infamously declared, “Kill three million of them, and the rest will eat out of our hands.”

The army targeted Dhaka University’s teachers and students, the core of the resistance, killing hundreds. Survivors recounted horrifying atrocities: slum dwellers gunned down as they fled burning homes, children witnessing their parents’ murders, and women abducted from dormitories. Journalist Anthony Mascarenhas, the first to report on the genocide internationally, quoted a Pakistani army major: “This is a war between the pure and the impure… They may have Muslim names, but they are Hindu at heart.”

According to a research paper published in the Security & Defence Journal titled ‘Genocide, Ethical Imperatives, and the Strategic Significance of Asymmetric Power: India’s Diplomatic and Military Interventions in the Bangladesh Liberation War (Indo-Pakistan War of 1971)’: The demand for independence in Bangladesh (then East Pakistan) was not initially universal, as pockets of support for Pakistan persisted.

Political groups like Jamaat-e-Islami and the Muslim League aligned with West Pakistan during the liberation war. Leaders such as Nurul Amin, Ghulam Azam, and Khwaja Khairuddin formed the Citizen Peace Committee, later called the East Pakistan Central Peace Committee (Shanti Bahini), which supported the Pakistani Army. Shanti Bahini facilitated the recruitment of Razakars, a paramilitary force notorious for war crimes, including kill lists targeting Bengali nationalists, intellectuals, and Hindus, as well as systemic rape and sexual slavery. With nearly 73,000 personnel, including Razakars, Al-Badr, and Al-Shams, these forces caused immense suffering, cementing the term “Razakar” as a symbol of betrayal in Bangladesh.

While Mukti Bahini fought for Bengali independence, Shanti Bahini supported Pakistan’s efforts to suppress the rebellion, creating a tragic divide among citizens. As civil war erupted, violence consumed the local population.

The role of the Razakars, local collaborators with the Pakistani military, was particularly heinous. Razakars were infamous for their brutal attacks on Hindu villages, aiding in mass killings, and abducting women for exploitation. Their involvement amplified the genocide, as highlighted in ‘The Blood Telegram’ by Archer K. Blood, where the systematic targeting of Hindus was explicitly described.

The genocide statistics are staggering:

Three million Bengalis were killed; 200,000 to 400,000 women were raped by the Pakistani military and collaborators; 10 million refugees fled to India; and over 942 killing fields were discovered across Bangladesh.

In 2024 the resurgence of ISI-backed Jamaat-e-Islami (JeI) in Bangladesh politics threatens both progressive forces in the country and Indian interests, given its five-decade-long record of fostering radicalism and supporting terror groups

Role of India: A humanitarian and strategic response

The Bangladesh Liberation War, lasting 13 days, witnessed significant contributions and sacrifices by India. Over 3,000 Indian soldiers lost their lives in the conflict, underscoring India’s resolute support for the liberation movement.

On December 16, 1971, approximately 93,000 Pakistani soldiers surrendered to the Indian forces marking the largest military capitulation since World War II. This decisive victory not only liberated Bangladesh but also showcased India’s commitment to defending human rights and supporting the oppressed.

India’s efforts included providing shelter to over 10 million refugees, extensive military and logistical support to the Mukti Bahini, and diplomatic manoeuvres to rally international backing for Bangladesh’s independence. The day is celebrated as Vijay Diwas, honouring the bravery and sacrifice of Indian forces and the shared vision of freedom.

On the present situation, India has strongly condemned the attack on Bangladeshi Hindus. During Indian Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri’s recent visit to Bangladesh, he reiterated India’s commitment to fostering strong bilateral ties, emphasising support for a stable, democratic, and inclusive Bangladesh. He raised concerns about recent attacks on cultural and religious properties, highlighting the importance of cooperation to address these challenges.

Plight of minorities: Then and now

The Liberation was marked by atrocities, with the Hindu minority disproportionately targeted. Fifty-two years later, targeted violence against Hindus in Bangladesh continues, including attacks on temples and forced conversions. The cycle of persecution has led to an alarming decline in the Hindu population in Bangladesh from 13.50 to 07.95 per cent. Reports from The Daily Star and human rights organisations document a pattern of mob violence against Hindus, echoing the horrors of 1971.

Lessons for present

While we remember the courage of the Mukti Bahini and the determination of the Bangladeshi people, we must also reflect on the failure of the world to protect the Hindus of Bangladesh in 1971. The international community’s inaction during that time must serve as a stark reminder that the protection of human rights remains a critical issue today.

This anniversary calls for urgent action from all governments and human rights organisations to ensure the safety and dignity of minorities, and to prevent further persecution and oppression. Let this be the wake-up call for the world to not fail the Bangladeshi Hindus again.

(IANS)