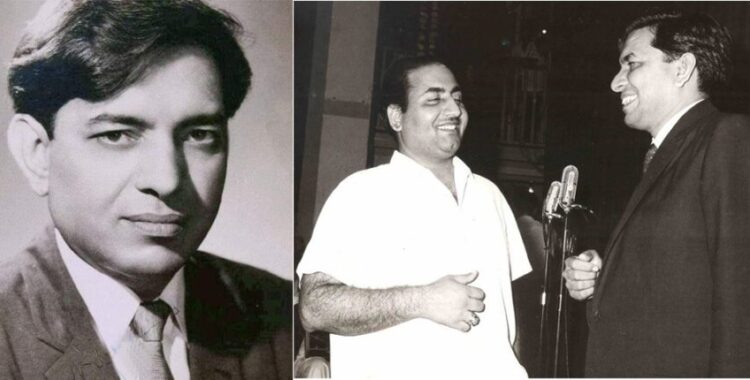

New Delhi: For a self-taught musician, it is rather impressive how his melodies underscored popular culture for a range of occasions in late 20th century India — be it children’s lullabies “Chandamama door ke” or “Chal mere ghode”, “Ham bhi agar bachche hote” for their birthdays, “Mera yaar bana hai dulha” and “Aaj mere yaar ki shaadi hai” for marriages, as well introducing Afghan and Arab strains into Hindi film music.

That was the talent of music composer Ravi, whose contributions went beyond providing enthralling music in films such as “Chaudhvin ka Chand” (1960), “Gharana” (1961), “Waqt” (1965), “Do Badan” (1966), and “Hamraaz” (1967).

To Ravi also goes credit for giving Asha Bhosle a prominent place in playback with songs ranging from playful “C A T cat, cat maane billii” (“Dilli ka Thug”, 1958) to wistfully romantic “Jab chali thandi hawa” (“Do Badan”) to the entrancingly philosophical “Aage bhi na jaane tu” (“Waqt”), as well helping Mahendra Kapoor evolve from yet another Mohd Rafi clone, and setting Shammi Kapoor on his rollicking career with songs like “Baar baar dekho” (“China Town”, 1962).

Born in Delhi on this day (March 3) in 1926, Ravi Shankar Sharma, or Ravi as he became known in the film industry, was interested in music from his childhood but received no formal training in it, picking up its nuances from hearing his father sing bhajans.

He also picked up prowess in various instruments on his own. Beginning his career as an electrician in the Post and Telegraph Department in Delhi, where he worked 1945-50, he used to occasionally sing on AIR.

He moved to Bombay in 1950 to become a singer in the film industry but found the going tough. While he used to sleep at railway platforms and outside shops, Ravi sustained himself with his skills as an electrician.

In an interview, he revealed he used to clean ceiling fans and get Rs 2 per piece and paid off loans from various people by repairing their electrical appliances!

However, he did not have to wait long, getting his first chance when S.D. Burman selected him for the chorus for a song (“Jhanak jhanak jhan jhan na..) in “Naujwan” (1951) and then, Hemant Kumar first used him in the chorus of the iconic “Vande Mataram” in “Ananda Math” (1952), and then, made him his assistant.

Ravi went on to help Hemant Kumar in films like “Shart”, “Jagriti”, and above all, “Nagin” (all 1954) – where he later revealed the iconic ‘been’ music in “Man dole mera tan dola” was derived from the music for the already recorded “Mera dil yeh pukare aaja..”

Ravi got his first break as an independent music composer with “Vachan” (1955) – where he also wrote the lyrics for “Chandamama door ke..” and also sang a duet with Asha Bhosle (“Yun Hi Chupke Chupke”).

He went on to get more films in the rest of the decade but the next notable one was “Dilli Ka Thug”, where apart from the ‘cat song’, he provided Kishore Kumar the perfect opportunity to showcase his zany side in “Ham to mohabbat karega”.

However, it was Guru Dutt’s “Chaudhvin Ka Chand” that enabled him to stand out.

Ravi, in a television interview, revealed that it took him “just 5 to 7 minutes” to fashion the music for the iconic title track, and that too, as he was returning home from work. He said he was thinking of the trend then to have one song use the film’s name when the tune came into his head and he called up lyricist Shakeel Badayuni and told him his idea.

As Ravi recited the beginning “Chaudvin ka chand ho…”, Shakeel added after a minute: “Ya aftaab ho..” and after another couple of minutes, completed it with “Jo bhi ho tum khuda ki kasam, laajawab ho”.

“Chaudvin ka Chand” proved to be a pace-setter for Ravi, in more way than one — for while it made his name in the Hindi film industry, it also brought him to the attention of southern producers. In the 1960s, he went on to score for many top movies, especially of B.R. Chopra.

While “Ae meri zohra jabeen..”, influenced by an Afghan folk song, and other songs of “Waqt”, the uplifting “Neele gagan ke tale”, “Na munh chupa ke jiyo”, and “Tum agar saath dene ka vada karo” in “Hamraaz”, and the Arabian-themed “Ghairon pe karam, apno pe sitam” in spy flick “Aankhen” (1968) still strike a chord, there are many more evergreen songs to his name.

Take the pensive “Chalo ik baar phir se, ajanabi ban jaaye” (“Gumrah”), the heartening “Ae mere dil-e-naadan, tu gham se na ghabrana” (“Tower House”, 1962), “Chhu lene do naazuk honthon ko” (“Kaajal”, 1965), bhajans “Jai Raghunandan jai Siyaram” (“Gharana”, 1961) and “Badi der bhayi Nandlala” (“Khandaan”, 1965), the “Garebon ki suno” (“Dus Lakh”, 1965), the philosophical “Sansar ki har shai ka itna hi fasaana hai” (‘Dhund”, 1973), “Tumhari nazar kyon khafa ho gayi” (“Do Kaliyaan”, 1968) and many more from his 100-odd films,

What distinguished Ravi’s music was how it could be simple, smooth yet profound simultaneously while he admitted that his aim was never to dictate to the lyricists, or drown the singer’s voice. Also, he never used Western musical instruments, confining himself to classical santoor, sitar, shehnai, and others.

Modest and self-effacing and well liked by all those he worked with, he never reached the height of his peers — or more importantly, seemed to aspire to these goals.

He only worked sporadically in the 1970s before making his comeback with “Nikaah” (1982) and then went to reinvent himself as a music composer for Malayalam films, ostensibly at the urging of singer Hariharan. He did some 15-odd films between 1986 and 2005, of which at least 10 were super hits.

Ravi spent his last years in contented retirement before passing away a few days after his 86th birthday in 2012, but remains firmly ensconsced in the hearts of music lovers since “Beete huye lamhon ki kasak saath to hogi”!

(IANS)