Dubai: In early October, images emerging from the dense forests of Bastar in Chhattisgarh marked a moment of quiet but significant change in India’s long-running battle against Left Wing Extremism.

According to a report by Khaleej Times, more than 180 Maoists, several of them carrying long-standing cash rewards, laid down their arms and entered state-run rehabilitation programmes.

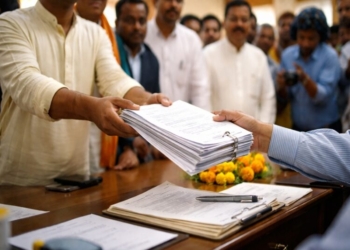

Weeks later, in Jagdalpur, over 200 more cadres, including around 110 women, surrendered along with 153 weapons.

Together, these developments point to a deeper shift: the diminishing pull of armed insurgency amid sustained security pressure and increasingly credible alternatives to violence.

Union Home Minister Amit Shah underlined this change in a post on X, stating that Abujhmarh and North Bastar—once considered Maoist strongholds—have now been declared free of Naxal presence.

He added that since 2024, over 2,100 Maoists have surrendered while 1,785 have been arrested, reaffirming the government’s stated goal of eliminating Naxalism by March 31, 2026.

The significance of these numbers becomes clearer when viewed against the movement’s history.

The Naxalite uprising began in the late 1960s, rooted in agrarian distress, land alienation and the perceived absence of justice in remote tribal regions.

Over time, it evolved into a prolonged insurgency that thrived on weak state presence and local disenchantment.

At its peak, Left Wing Extremism extracted a heavy toll on lives and development.

However, the decline has been steady.

The Khaleej Times report further said that incidents of LWE violence, which peaked at 1,936 in 2010, dropped to 374 in 2024—an 81 per cent reduction.

Fatalities fell even more sharply, from 1,005 deaths in 2010 to 150 last year, it added.

Multiple factors explain this turnaround. Sustained, intelligence-led operations by central forces and state police have weakened Maoist leadership and logistics.

Simultaneously, policy has evolved beyond a purely military response.

As per the report by Khaleej Times, surrender-and-rehabilitation schemes offering financial assistance, skill training and reintegration have signalled a viable civilian future for cadres willing to exit violence.

Equally crucial has been the erosion of local support. As roads, healthcare access and governance reached previously neglected areas, communities increasingly rejected the instability imposed by armed groups.

While the recent surrenders do not mark the end of the insurgency, they reflect a decisive shift.

For the first time in decades, the prospect of lasting peace in affected districts appears within reach.

(IANS)