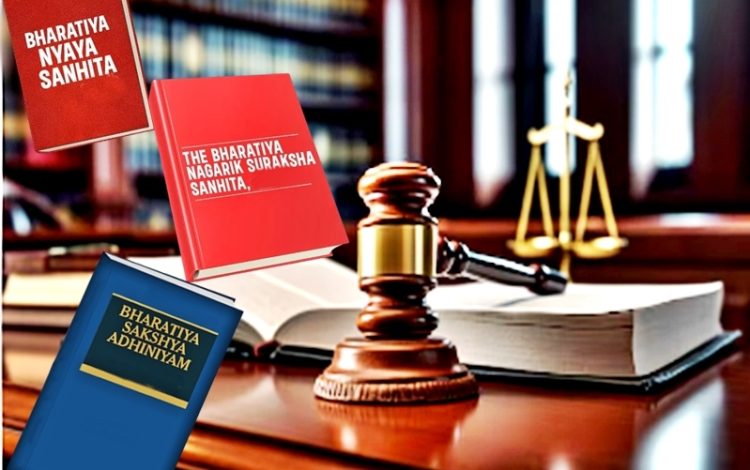

New Delhi: India’s criminal justice system underwent a significant transformation with the implementation of three new laws — Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), and Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam (BSA).

These laws, which came into force on Monday, replaced the longstanding British-era statutes: the Indian Penal Code (IPC), Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC), and the Indian Evidence Act.

All across the country, new FIRs were registered under these modernised laws, marking a departure from the previous legal frameworks. However, cases filed before July 1 will continue under the old laws until they reach their final conclusion.

The journey towards these reforms began six months ago when the laws were enacted, following extensive consultations with key stakeholders such as Supreme Court judges, governors, civil servants, police officers, and lawmakers.

Union Home Minister Amit Shah played a pivotal role, conducting 158 meetings and incorporating around 3,200 suggestions into the drafting process.

The laws were scrutinised by a Parliamentary committee, with most recommendations being accepted before being presented to Parliament for approval. The consultation process took four years before enactment of the laws six months ago.

Key features of the new laws include:

Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) has been streamlined to 358 sections, down from 511 in the IPC, incorporating 21 new crimes, increased penalties for 82 offences, and introducing minimum punishments for 25 crimes.

Duration of imprisonment has been extended in 41 crimes.

Moreover, community service has been introduced as a penalty in six crimes. Around 19 sections have been removed.

Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) now comprises 531 sections, with modifications to 177 sections, including additions of nine new sections and 39 sub-sections, and deletions of 14 sections.

Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam (BSA) replaces the Indian Evidence Act (166 sections) with 170 sections, making changes to 24 sections and adding two new sub-sections while removing six sections.

Earlier, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had articulated the ethos behind these reforms as “citizen first, dignity first, and justice first,” emphasising a shift from traditional policing methods (‘danda’) to modern data-driven approaches.

The new laws also prioritise swift justice for crimes against women and children, ensuring completion of investigations within two months of filing. Victims are entitled to regular updates on their cases within 90 days, and courts are empowered to limit adjournments to expedite proceedings.

In Parliament, Amit Shah underscored that the focus of these reforms is on enhancing justice delivery while safeguarding the rights of both victims and accused individuals, moving away from punitive measures alone.

The overhaul aims to rid the legal system of colonial-era vestiges and enable online reporting of crimes, allowing for more accessible and transparent law enforcement.

These legislative changes mark a significant step towards modernising India’s criminal justice system, aligning it with contemporary needs and global standards.