New Delhi: Pakistan has criticised Ajay Bisaria, India’s former high commissioner to Islamabad, for allegedly presenting a “fictitious narrative” surrounding the February 2019 Balkote crisis in his recently published book, ‘Anger Management’.

“It appears that the book seeks to advance India’s fictitious narratives around the developments of February 2019 and the usual chest thumping that Indian officials have adopted as their default narrative,” a spokesperson for the Pakistan government said during a press briefing in Islamabad.

On August 7, 2019, Pakistan expelled Bisaria from Islamabad — it was the first time an Indian head of mission was declared persona non grata and asked to leave by Pakistan.

Bisaria, who had served as late former prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s private secretary, was India’s high commissioner to Pakistan from 2017 to 2020. It was during his tenure that the Balakote crisis erupted.

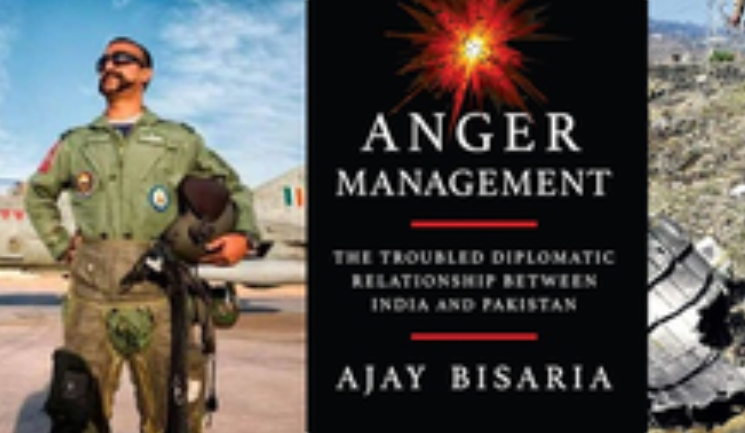

He notes in his book, ‘Anger Management: The Troubled Diplomatic Relationship Between India and Pakistan’, how an angry Prime Minister Narendra Modi refused to take the call of his then Pakistani counterpart, Imran Khan, who had wanted to lower the political temperature.

In his criticism of the book, the spokesperson for Pakistan noted that “it is a matter of common knowledge that the ruling dispensation in India used the Pulwama episode for domestic political gains.”

He pointed out that as the Lok Sabha elections draw closer, it is not surprising that “a Pakistan bashing, jingoistic and militaristic narrative is being unleashed in India”.

The spokesperson added: “Mr Bisaria knows very well that Balakot was a military fiasco for India. It was an instance of Indian adventurism that went badly and embarrassingly wrong for them as Indian aircraft were shot down, and an Indian pilot was taken prisoner by Pakistan.”

Continuing his diatribe, the spokesperson said: “It is also very shocking that a professional diplomat is advocating coercion and use of force as a means to conduct diplomacy. This reflects the rise of a fascist mindset in India. It also demonstrates that India is not ready to assume the important responsibilities that it so desires on the global stage.”

Responding to the criticism, the publisher of the book, David Davidar, said the angry response of Pakistan only goes to “show the importance of Bisaria’s revelations about and analysis of the diplomatic relationship between India and Pakistan”.

Davidar added that he hoped the book would be widely read and discussed, including in Pakistan.

In his account of what happened then, Bisaria writes that an intense phase of diplomacy began soon after the Pulwama attack in Kashmir in which New Delhi shared its outrage with the international community.

In South Block, the MEA had drafted a comprehensive response aimed at Pakistan, reminding the world that it was “a well-known fact that Jaish-e-Mohammad and its leader Masood Azhar are based in Pakistan”. It was in response to Imran Khan’s address to his nation on February 19, 2019.

Bisaria writes that as the Saudi Crown Prince and Prime Minister, Mohammed Bin Sultan, travelled from Pakistan to India on February 21, PM Modi shared India’s anguish with him, telling him publicly that punishing terrorists and their supporters was important for both countries.

Continuing with its diplomatic push, the author narrates how India suggested to Japan that it should consider postponing the scheduled visit by Pakistan’s then Foreign Minister Shah Mehmood Qureshi, or if he did show up, to highlight the terrorism issue. Qureshi eventually canceled his Tokyo trip.

Bisaria claims that Pakistan was bracing itself for such action by India, but did not know when and in what shape it would come.

He also notes that the then Pakistan Army Chief Qamar Javed Bajwa may not have known about the specific operation that took place in Pulwama, but it was likely that the operation had been cleared by the DG, Inter-Service Intelligence (ISI).

“General Bipin Rawat told me that the retaliatory attack that India was planning would be much bigger than the surgical strikes of 2016 and it was coming soon enough,” the author claims.

Bisaria also writes that Rawat believed Pakistan’s corps commanders were not too happy with the Bajwa doctrine, for it seemed to be diluting traditional postures and that affected staff morale.

IANS