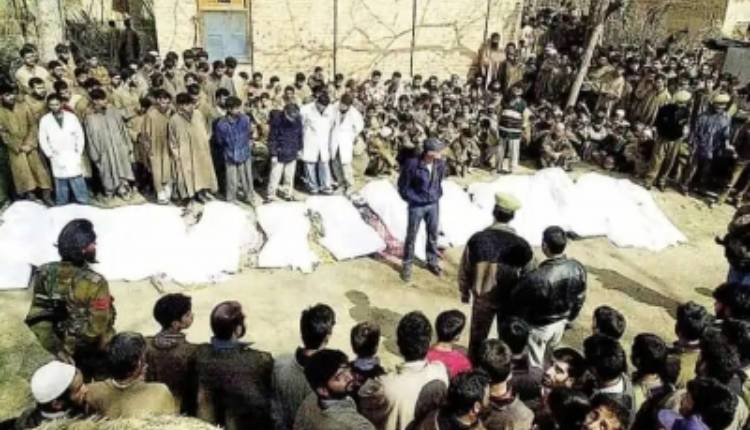

New Delhi: As the Kashmiri Pandits observe January 19 as the exodus day, theirs is a story that needs to be retold and conveyed to know how the so-called -movement for “Azadi (freedom)” was camouflaged for carrying out religious persecution.

The mass exodus of the Hindus from the valley was not an overnight happening. It did not take place in one night in January but happened during a period when terrorism and separatist sentiment took over the political and administrative setup in the valley and the leaders in that period failed their duties, whether they were in the Centre or the then Jammu and Kashmir state.

January 19 manifests the pain of a community which lost its homeland and continues to await justice.

Some true accounts of those who suffered in targeted and motivated violence in Kashmir.

On the night of January 19 (intervening January 20), 1990, mayhem erupted in the valley streets as loudspeakers atop mosques started blazing out venom against the minorities, especially the Hindus. The turn of events on this night set in motion the wave of exodus.

Recalling the events of the frightful night, 80-year-old Rajni Dhar, who lived in a three-storey house in Chota Bazar, Srinagar, said, “It was around 10 p.m. in the cold dead night of January 19, 1990. There was no electricity. Darkness ruled outside. Inside the house the lone flickering kerosene lamp had three pairs of eyes glued to it as the simmering coals in the ‘Kangri’ (firepot) kept each of them warm. The silence was ruptured by a lone stone that shattered the window pane and jolted the three out of the moment with something eerie brewing from that pelting.”

“Voices emanating from nowhere were getting louder by every second. All at once loudspeakers started blazing as if in an orchestrated manner. In the beginning, we were confused but soon it became very clear. Slogans against India and Kashmiri Pandits were being raised. Loudspeakers from mosques were asking the majority Muslim community to come onto the streets. We three — me, my husband and my mother-in-law were horrified. There was nothing we could do,” said Dhar.

“‘We want Kashmir without Hindu males but with Hindu females’, ‘Indian dogs go back’, ‘Infidels and kafirs go back or face death’, ‘we want Nizam-e-Mustafa’ here, screamed the men as the sound echoed all over the valley. Thousands of protesters were on the roads. All of a sudden tin sheeted roofs of houses were being beaten all around. It was as if some kind of death dance was being conducted,” she recalled.

“There were no police and the state administration had abandoned us. I was petrified with the thought that we could be attacked. This continued way past midnight. We were resigned to our fate. Around 2 a.m., sirens brought a glimmer of hope. Army and BSF columns were spreading out on the streets. Tears filled our eyes as life seemed to have got a second chance. By the time it was dawn, things had changed forever for us minority Kashmiri Pandits. Many started fleeing…”

This is not an excerpt from a novel or film script. It is a true account of Rajni Dhar. Her husband, Late Maharaj Krishen Dhar, a resident of Srinagar’s Chota Bazar area and former Principal of a local public school, was an eyewitness to the horror of that fateful night.

Almost all relatives of Dhar fled the valley in the following days, but the family tried to stay put in their ancestral home.

The killing of their neighbour, telecom engineer B.K. Ganjoo on March 22, 1990, scared the Dhar family. They were grief-stricken as the young engineer was a soft-spoken person and harmed no one. “His brutal killing instilled fear in us. He and his family were close friends. It was unbelievable that his neighbours were also involved in his murder. Still, we did not think of leaving our home,” said Dhar

In April 1990, when her husband was asked to leave the valley by his Muslim neighbours saying they couldn’t guarantee the safety of the family any further. Dhar had no option but to flee. The family left all their property and belongings behind.

“Some of those very neighbours later looted our house and set it on fire. We lost everything,” she said.

Naveen Kundu lived with his parents in Srinagar’s posh area of Indira Nagar. Even though his father, a bank manager, got threats, he did not leave the Valley. But, the targeted violence forced the young Naveen to flee Kashmir in April 1990.

“I can never forget those days of fear and hopelessness. My immediate neighbour in Srinagar, D.N. Chaudhary was kidnapped, and killed and then his body was thrown in the verandah of his house. It was traumatic,” he added.

Dr Sushma Shalla Kaul’s father was kidnapped, tortured and killed mercilessly. “My father was a CID officer. His own PSO betrayed him. On May 1, 1990, he was kidnapped, and tortured, his nails and hair were pulled out, his body bore burnt marks and then he was shot dead. We got his body on May 3 and we left Kashmir on May 6. We have never gone back,” she said.

“My mother was a teacher, so we got staff quarters. Here my neighbours were the relatives of two other victims — Girja Tickoo, who was brutally gang-raped and cut by a saw machine even as she was alive; and Prana Chatta Ganjoo and her husband whose body was found but Prana’s body has never been found. We all had the same grief and we children grew together,” she added.

Bollywood actor Rahul Bhat’s family fled the valley in fear when the terrorism had started raising its head in 1989.

An original resident of Vicharnag, a very holy place for Kashmiri Pandits, Bhat’s village witnessed the first killing when an 85-year-old priest of the ancient temple was bludgeoned to death by a Muslim guard with the butt of a gun.

“We all heard wails and everyone rushed. The man was arrested. The next day a hit list was issued wherein the names of all those who had reached the temple after the murder were mentioned. When the fear became real, my family left in September 1989, much before the rest from the Valley fled,” he said.

Rakesh Bhatt, who used to live in the Chanapora area of Srinagar city says: “I get goosebumps when I remember the night of January 19 in particular. My parents had left for Jammu because of the Darbar move and I had my elder sister with me. I was just 19 years old then. We were so scared of the slogans and the stone pelting that I hid my sister in the attic. We just wanted to run away to our parents but could not summon the courage to do it, to go out as I feared for my sister. Finally, after a few days, I somehow managed to flee with my sister from my own house and from my own Muslim neighbours.”

Santosh Dullo remembers those days when she found a ‘threat notice’ pasted on the entrance of her house. A few days later the uncle of her husband was shot dead near the house, perhaps mistaking him to be Santosh Dullo’s husband Late Dr U.K. Dullo, who was a Professor in the Srinagar Women’s College. The Dullo family had no choice but to flee.

Jawahar Lal Bhan, an engineer in the Irrigation Department of the J&K government was busy constructing a new house for his family in the Baghat-Barzulla area of Srinagar. He got a rude shock when a colleague told him that he was on the terrorists’ hit list and should leave. The Bhan family fled the valley after handing over the keys to his new house to his colleague. He never got the house back.

(IANS)