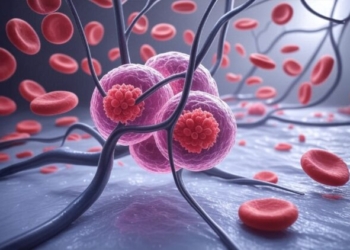

London: Six pets in Portugal and one in the UK were carrying antibiotic-resistant bacteria similar to those found in their owners, according to a study.

Dogs, cats and other pets are known to contribute to the spread of antibiotic-resistant pathogens that can cause human disease.

In the study, researchers at the University of Lisbon in Portugal found bacteria resistant to third generation cephalosporins and carbapenems in dogs and cats and their owners.

Cephalosporins are used to treat a broad range of conditions, including meningitis, pneumonia and sepsis, and are classed among the most critically important antibiotics for human medicine by the World Health Organisation (WHO). Carbapenems are part of the last line of defence when other antibiotics have failed.

The finding underlines the importance of including pet-owning households in programmes to reduce the spread of antimicrobial resistance, said researchers.

“In this study, we provide evidence that bacteria resistant to third generation cephalosporins, critically important antibiotics, are being passed from pets to their owners,” said Juliana Menezes from the varsity’s Faculty of Veterinary Medicine.

“Owners can reduce the spread of multidrug-resistant bacteria by practising good hygiene, including washing their hands after collecting their dog or cat’s waste and even after petting them,” Menezes said.

The team tested faecal samples from dogs and cats and their owners for Enterobacterales (a large family of bacteria which includes E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae) resistant to common antibiotics.

The prospective longitudinal study involved five cats, 38 dogs and 78 humans from 43 households in Portugal and seven dogs and eight humans from seven households in the UK.

In Portugal, one dog was colonised by a strain of multidrug-resistant OXA-181-producing Escherichia coli. OXA-181 is an enzyme that confers resistance to carbapenems.

Three cats and 21 dogs and 28 owners harboured ESBL/Amp-C producing Enterobacterales. These are resistant to third generation cephalosporins.

In eight households, two houses with cats and six with dogs, both pet and owner were carrying ESBL/AmpC-producing bacteria.

In six of these homes, the DNA of the bacteria isolated from the pets (one cat and five dogs) and their owners was similar, meaning these bacteria were probably passed between the animals and humans. It is not known whether they were transferred from pet to human or vice versa.

In the UK, one dog was colonised by multidrug-resistant E. coli producing NDM-5 and CTX-M-15 beta-lactamases.

These E. coli are resistant to third generation cephalosporins, carbapenems and several other families of antibiotics.

ESBL/AmpC-producing Enterobacterales were isolated from five dogs and three owners.

In two households with dogs, both pet and owner were carrying ESBL/AmpC-producing bacteria. In one of these homes, the DNA of the bacteria isolated from the dog and owner was similar, suggesting the bacteria probably passed from one to the other. The direction of transfer is unclear.

All of the dogs and cats were successfully treated for their skin, soft tissue and urinary tract infections.

The owners did not have infections and so did not need treatment.

The study will be presented at the ongoing European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (ECCMID) in Copenhagen, Denmark.

(IANS)