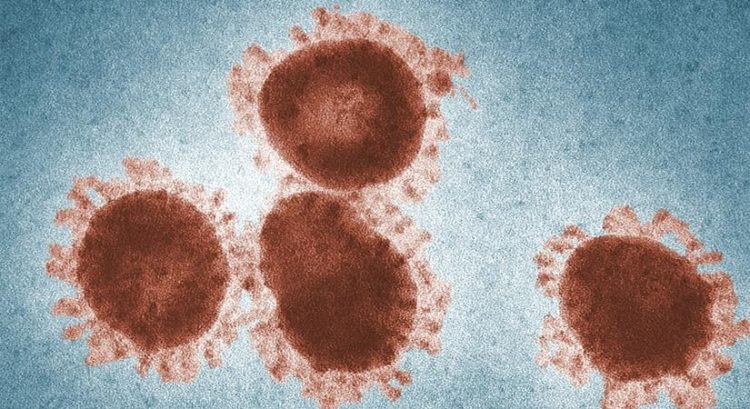

London: Researchers have found an unexpected link between tuberculosis and cancer, which may lead to new drug treatments for the bacterial disease that kills more than 1.5 million people each year globally.

The study, led by researchers at Stanford Medicine, found that lesions called granulomas in the lungs of people with active tuberculosis infections are packed with proteins known to tamp down the body’s immune response to cancer cells or infection.

Some types of cancer drugs target these immunosuppressive proteins.

Because these medications are widely used in cancer patients, the researchers expect that clinical trials can be launched quickly to test whether they can combat tuberculosis infection.

Tuberculosis affects millions of people around the world, and it is difficult to cure even with extended antibiotic therapy.

“Tuberculosis is a massive global health burden,” said Erin McCaffrey, lead author and graduate student at the varsity.

“Most of the time, the immune system is unsuccessful in eradicating the bacteria, but it’s not known why. We wondered whether the same molecular pathways that protect cancer cells from the immune system could also be affecting the immune response to the tuberculosis bacteria,” McCaffrey said.

The researchers used an imaging technique called multiplexed ion beam imaging by time of flight (MIBI-TOF).

Using the technique, they mapped the location of immunosuppressive proteins in granulomas in lung and other tissue from 15 people with active TB.

“We saw some of the brightest signals we’d ever seen, even in comparison with cancer tumours,” said Mike Angelo, assistant professor of pathology at Stanford University Medical Center.

“This indicates the near-universal presence of key immunosuppressive proteins in the granulomas,” Angelo said in the study published in the journal Nature Immunology.

In particular, the researchers saw high levels of two proteins – PD-L1 and IDO1 – that can suppress the immune response to cancer and are often found in tumour tissue. These proteins are targeted by approved cancer drugs.

When McCaffrey and Angelo studied blood samples collected from more than 1,500 people infected with TB, they found that the levels of PD-L1 correlated with clinical symptoms.

Patients with latent, or asymptomatic, infection had lower levels of PD-L1 in their blood and were less likely to progress to active infection than those with higher PD-L1 levels.

Conversely, patients with active infection who were considered cured after treatment experienced significant decreases in their blood PD-L1 levels compared with those who were not cured.

“We saw really consistent upregulation of these signals in the blood, which is emblematic of the failed immune reaction,” Angelo said. “They could also be used to predict disease progression from latent to active disease.”

(IANS)