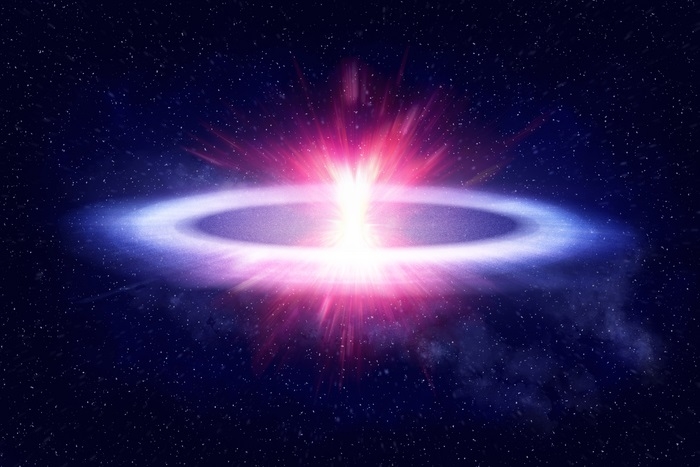

London: Astronomers have observed an explosion as big as our solar system but similar to that of an extremely flat disc.

The explosion, which occurred 180 million light years away, challenges our current understanding of explosions in space, said researchers from the University of Sheffield in the UK.

The explosion was a bright Fast Blue Optical Transient (FBOT) — an extremely rare class of explosion which is much less common than other explosions, such as supernovas. The first bright FBOT was discovered in 2018 and given the nickname “the cow”.

Explosions of stars in the universe are almost always spherical in shape, as the stars themselves are spherical. However, this explosion is the most aspherical ever seen in space, with a shape like a disc emerging a few days after it was discovered.

This section of the explosion may have come from material shed by the star just before it exploded, the researchers said.

“There are a few potential explanations for it: the stars involved may have created a disc just before they died or these could be failed supernovas, where the core of the star collapses to a blackhole or neutron star which then eats the rest of the star,” said lead author Dr Justyn Maund, from the University’s Department of Physics and Astronomy.

While it’s still unclear how bright FBOT explosions occur, the researchers hoped that the new observation, published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, will bring us closer to understanding them.

“Very little is known about FBOT explosions — they just don’t behave like exploding stars should, they are too bright and they evolve too quickly. Put simply, they are weird, and this new observation makes them even weirder,” said lead author Dr Justyn Maund, from the University’s Department of Physics and Astronomy.

“Hopefully this new finding will help us shed a bit more light on them — we never thought that explosions could be this aspherical.

“What we now know for sure is that the levels of asymmetry recorded are a key part of understanding these mysterious explosions, and it challenges our preconceptions of how stars might explode in the Universe,” Maund said.

Scientists made the discovery after spotting a flash of polarised light completely by chance. They were able to measure the polarisation of the blast — using the astronomical equivalent of polaroid sunglasses — with the Liverpool Telescope (owned by Liverpool John Moores University) located on La Palma Observatory.

By measuring the polarisation, it allowed them to measure the shape of the explosion, effectively seeing something the size of our Solar System but in a galaxy 180 million light years away. They were then able to use the data to reconstruct the 3D shape of the explosion, and were able to map the edges of the blast – allowing them to see just how flat it was.

The mirror of the Liverpool Telescope is only 2.0m in diameter, but by studying the polarisation the astronomers were able to reconstruct the shape of the explosion as if the telescope had a diameter of about 750km.

(IANS)