Chandigarh: Twenty-two years ago, a Canadian-born Indian woman, Jassi, paid a heavy price for defying her parents to marry a poor peasant from Jagraon in Punjab.

She was kidnapped, defaced and killed. Her husband, Sukhwinder Mithu, survived the murderous attack on him but has been a living corpse since then.

On one side, he’s fighting for justice for Jassi, and on the other, he’s fighting the influential persons, ‘corrupt’ police who slapped one after another seven ‘false’ police cases on him.

All this to make him submit.

Mithu has already been acquitted in six of those cases, and the Commission for Inquiry into false police cases upheld his innocence along with an award of compensation of punishment for guilty cops.

However, the orders issued by Justice Mehtab Singh Gill (retd.) are yet to be implemented. Jassi’s mother and uncle, Malkiat Kaur and Surjit Badesha, were extradited for the crime in January 2018, 18 years after Jassi’s murder. Their trial has been going on since then in a Sangrur court.

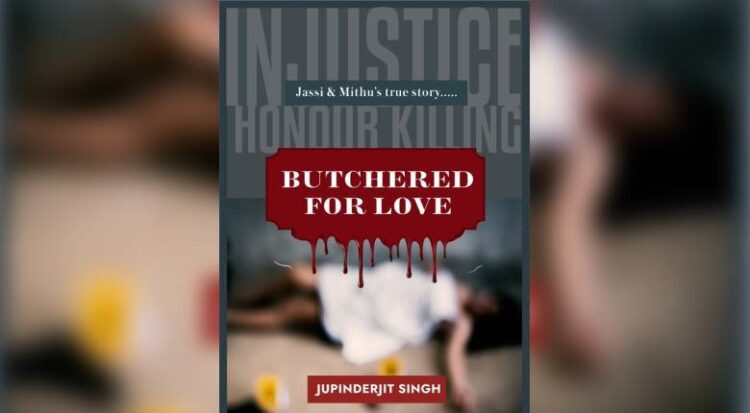

Investigative journalist Jupinderjit Singh has brought out Mithu’s suffering and Jassi’s gruesome honour killing in his book ‘Butchered for Love’ (FernTree Publishing), which was released at Inkreadible Writer’s Fest last week.

Written from the point of view of different characters involved in the story, the book narrates Jassi and Mithu’s immortal love tale, including the letters they wrote, the sweet-nothings they shared, and just about a month of togetherness they had before the contract killers swooped like vultures on them.

The book paints a gory yet accurate picture of the menace of honour killing in India. “It is a dishonourable killing,” Jupinderjit Singh told IANS while talking about the book.

A chronicler of the case for more than two decades now, Jupinderjit Singh has written 100-plus news articles about it. His reports appearing in The Tribune were taken up further by foreign journalists as well. His earlier work included the discovery of the lost pistol of Shaheed Bhagat Singh, with which the martyr killed British Police Officer J.P. Saunders in December 1928.

“I have seen much bloodshed and macabre killings, but the way Jassi was killed disturbed me the most,” he said.

Sample this excerpt from the book, “Even if you had the hardest heart in the world, you would tremble at the marks on Jassi’s body. Using a sword, the killers had made three deep horizontal cuts. First, a 7.5-inch long and two-inch wide across her face, cutting the nose into two. Then, below the neck was a 4 x 2.5-inch slit mark that had caused her death. When your throat is slit, you can’t even scream because the blood enters your air pipe and lungs, asphyxiating you within seconds.

“At best, Jassi could have only gurgled her agony. It didn’t end there. Another deep horizontal cuts, 6.5-inche long and 2.5-inch wide across Jassi’s breasts. A punishment for going against the wishes of her parents. They called it an act of saving the family’s honour. But where’s the honour in this?”

Jupinderjit Singh’s questions in the book, “I wonder if the hearts of the contract killers didn’t bleed for a moment when Jassi was crying, beckoning God and humanity, and compassion in them when they were killing and ravaging her. Or didn’t they even think about their sin when they left Mithu for dead in the fields and snatched his Jassi forever from him? Just a few thousand currency notes were enough to make them beasts.”

Jassi’s life was killed in the bud.

Speaking for oppressed and suppressed women who can’t choose their life partner even in the modern world, Jupinderjit Singh writes, “Jassi lived chasing a dream, and she died doing so. She was a free bird, and no one could clip her wings. She and Mithu were born miles away and nurtured in completely contrasting conditions. But while they narrowed the gap of continents between them, they could not win over the narrow-minded people and eventually paid for it dearly.”

(IANS)