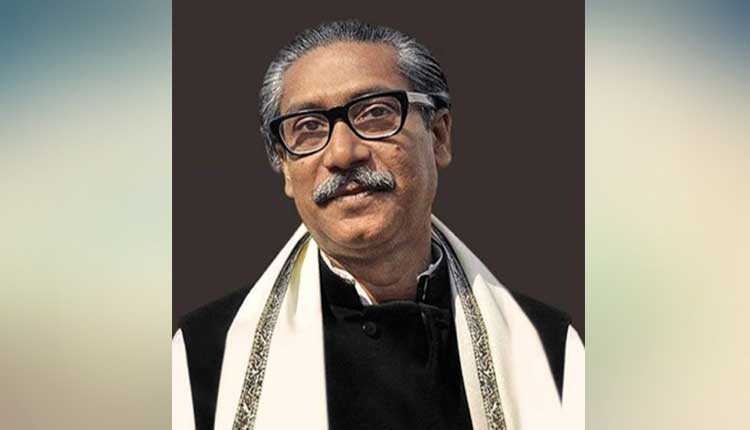

New Delhi: On 15 August 1975, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, founding father of Bangladesh, was assassinated along with most members of his family by renegade soldiers of the Bangladesh army. The murder of Bangabandhu, as he is revered in Bangladesh, pushed the country into an era of lawlessness typified by coups, counter-coups and blatant moves to provide protection to the assassins by successive military and quasi-military regimes in the country.

For twenty-one years following the tragedy, Mujib’s role in the formation of the Bangladesh republic was deliberately airbrushed out of the national historical narrative. There was no mention either of the role of his political associates who had formed a government-in-exile in April 1971 and waged war against Pakistan’s occupation army in Bangladesh. For Bangladesh’s people, the assassinations of 15 August and later of four national leaders on 3 November of the year were a calamity in that the country was pushed into political medievalism.

The national slogan of Joy Bangla was replaced by the Pakistan-style ‘Bangladesh Zindabad.’ Worse, Bengali nationalism which powered the Bengali struggle for liberation was sought to be replaced, by the regime of Bangladesh’s first military dictator Ziaur Rahman, by a spurious ‘Bangladeshi nationalism’. The country’s second military dictator Hussein Muhammad Ershad went a step further through imposing Islam on the country as the religion of the state. Thus was the secular identity of the state badly undermined.

The Zia regime sent off a number of Mujib’s assassins to Bangladesh missions abroad as diplomats; and the Ershad dispensation permitted the killers to form a political party and take part in presidential elections. In the era of Zia’s widow Khaleda Zia, notorious collaborators of the Pakistan occupation army in 1971 were inducted in the cabinet as ministers and political advisors.

The indemnity ordinance which constitutionally blocked any trial of Bangabandhu’s assassins was repealed when Sheikh Hasina led the Awami League back to power in 1996. To date, six of the killers have been tried and executed, while five more are on the run. It is assumed that some of them are in Africa or in Pakistan. One is in the United States and another is in Canada. In effect, justice over the 15 August tragedy will not be fully done until all these absconding assassins are brought to Bangladesh and have the sentences served on them implemented under the law.

With another anniversary of the 15 August assassinations approaching, there are some significant questions which call for responses in Bangladesh. And these questions relate to the elements who planned the conspiracy, eventually emerging as the beneficiaries of the assassinations. The Bangladesh government is yet to initiate any move to prosecute these individuals, posthumously of course, since they have by now died of natural causes.

The first question revolves around the role of Khondokar Moshtaq Ahmed, Mujib’s long-time colleague and minister for commerce at the time of the 15 August coup. Reports have persisted of Moshtaq and three others — Taheruddin Thakur, minister of state for information, Mahbub Alam Chashi, a Moshtaq loyalist, and ABS Safdar, national security chief — holding meetings at the Bangladesh Academy for Rural Development (BARD) in Comilla in the days immediately preceding the assassinations.

On the morning of 15 August, Moshtaq and Thakur appeared at Bangladesh Radio, with Thakur busily issuing instructions on the steps the new regime, headed by Moshtaq as President, would be taking in the aftermath of the political changeover.

No inquiry has in all these forty-eight years since the assassinations been ordered into the role of these men in the plot to overthrow the government of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and murder him in the process. Neither has there been any move to investigate the failure of the various security agencies to prevent the coup.

Or could it be that all these agencies were in the know and therefore did not inform the government that a conspiracy was afoot against it? Such questions arise in light of the fact that when his residence came under attack in the pre-dawn hours, Bangabandhu himself tried calling the agencies. No one responded.

Justice therefore demands that a full-scale inquiry be launched into the entire web of conspiracy which caused the tragedy in August 1975. General Ziaur Rahman, at the time deputy chief of army staff, was approached by the conspiring majors and colonels on behalf of Moshtaq twice, in November 1974 and March 1975, with appeals for him to be part of their plan.

Zia apparently declined and told them to do what they thought they needed to do. As the second, and serving, senior-most officer in the army, it ought to have been his responsibility to inform the government of what was going on. He failed to do that. His role calls for judicious investigation.

Meanwhile, General K.M. Shafiullah, the chief of army staff, remained blissfully unaware of the plans that were being finalised to bump off Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s government. He failed to protect the President, that is Bangabandhu, and even in the minutes and hours following the carnage at Mujib’s residence badly failed to take action against the assassins.

In all these decades since the bloodletting, questions have abounded about the failure of key officers in the army to keep track of what was going on prior to 15 August 1975. Once the coup had come to pass, not one of them moved against the assassins but with alacrity proclaimed their loyalty to the illegitimate regime of Khondokar Moshtaq Ahmed.

As the people of Bangladesh prepare to observe yet one more anniversary of what surely was one of the darkest moments in their history, it is important that these unresolved questions be answered to full public satisfaction. The mid-ranking military officers who carried out the coup against Bangabandhu’s government certainly had political and other backing behind them. And, yes, officials at the United States embassy in Dhaka held a series of meetings with the assassins before the coup. That phase of the plot has yet to be focused on.

Of the truckloads of soldiers who swarmed the Mujib residence on 15 August, a good number of them are yet alive and growing old. They need to be identified, tracked down and brought to trial, along with everyone else — from Moshtaq down to all the beneficiaries of the assassinations in posthumous manner and otherwise— if rule of law is to be restored in Bangladesh, if the sanctity pf constitutional government is to be preserved, if the nation’s secular ethos is to be upheld.

(IANS)